Building a Reactive Architecture Around Redis

Using Redis’ features to generate a reactive data-flow

Redis is one of the most powerful and versatile pieces of technology I’ve come across. Sadly, most people only know it because it makes for a good caching solution.

We need to fix that.

In particular, I want to show you that you can create a reactive architecture having Redis as the main component. This is a huge plus, especially if you already have it as part of your infrastructure due to other requirements (i.e the good ol’cache).

What you use with Redis to interact with the features I’ll be describing here is up to you, honestly at this point any option is as valid as the next one. I tend to prefer using Node.js but that’s me, you’re free to use whatever works best for you.

PermalinkBuilding a reactive architecture

The first thing to understand here is what exactly is a reactive architecture, and why would we want to build one instead of going for a more traditional approach?

Simply put, a reactive architecture is one where every bit of logic gets executed the moment all its pre-conditions are met — I guess I should’ve added quotes around the word “simply”.

Let me put it another way: when you need your logic to be triggered after a particular event happens, you have two options:

- Keep checking some kind of flag in regular intervals until it’s ON, meaning the event happened.

- Sit and wait, until something else notifies your service that the event was triggered.

The second part is the key to the Observer pattern in Object Oriented Programming. The observed object lets everyone interested in its internal state know, that it, in fact, was updated.

What we’re trying to do here, is to extrapolate that same OOP pattern into an architecture-level design. So instead of having a bit of logic within our program, I’m talking about having a service’s function be triggered once the right event happens.

This is the most efficient way to distribute and scale a platform, due to the fact that:

- You don’t have to waste time and network traffic polling a data source for a particular flag (or whatever you feel like you should be polling). Besides, unrequired polling could cause extra expenses if you’re on a pay-per-use infrastructure, unneeded work on the target service and you might end up having to aggregate events if more than one happens during the time your code is waiting to poll.

- You can scale up the processing power of the services by adding new ones, working in parallel, and capturing events as fast as they possibly can.

- The platform is more stable. By working reactively, you can be sure that your services will work at the optimal speed without fear of crashing due to data overload from a client.

Reactive platforms are inherently asynchronous, so any client application that attempts to work with them, needs to also adapt to the same paradigm. The external API might be REST through HTTP, but that doesn’t mean you’ll get your answer as a response, instead, you’ll get a 200 OK response meaning that your request was received. For your application to get the actual results, it’ll have to subscribe to the particular event that will contain such a response.

Keep that in mind, otherwise, you’ll spend a long time debugging why you’re not getting the response you want.

PermalinkWhat do we need then?

With that out of the way, what do we need to make our platform/architecture a reactive one? It’s not ReactJS, that’s for sure. We need a message broker, something that will centralize message distribution between multiple services.

With something that can act as a broker, we need to make sure our code is written in a way that it can subscribe to certain events by letting the broker know where it is, and the type of events it needs.

After that, a notification will be sent to our service, and our logic will be triggered.

Sounds easy right? That’s because it is!

PermalinkHow does Redis factor in here then?

Redis is so much more than a key-value in-memory store, in fact, it has 3 features I love about it and that allow me to create reactive architectures based off of different expected behaviors.

Those 3 features are:

- Pub/Sub. Redis has a message queue inside, which allows us to send messages and it’ll distribute them to every subscribed process. This is a fire&forget type of contract, which means if there are no listeners active, then the message will get lost. So take that into consideration when using this channel.

- Keyspace notifications. Probably my favorite feature from Redis. These bad boys are events created by Redis itself and distributed to every process out there that decided to subscribe to them. And they are about changes on the keyspace, meaning, anything that happens with the data you have stored inside it. For instance, the moment you delete a key, or update it, or when it gets deleted automatically once its TTL counter reaches 0. This allows you to generate timed events. Did you ever have to trigger a bit of logic 3 days after “something” happened? This is how.

- Redis streams. This is a mixture of Redis’ data types, mixed with keyspace notifications and pub/sub, all put together and working great. Streams try to emulate the behavior a

tail -fcommand would have on your terminal. If you’ve never seen that command, that’s a *nix command that shows you the last line of a file, and stays listening for changes on the file, so that when you add a new line, it’ll list it right away. The same happens with streams. They’re very powerful and incredibly useful given the right use case. You can read more about them here.

All these features allow you to communicate with your processes in one way or another and depending on the type of behavior you’re after, you might want to tackle one, or all of them.

Let’s take a quick look at some examples that will give you an idea of what to use and when.

PermalinkClassic event-based messaging

The easiest example is one where every microservice out there is waiting for something to happen. An event to be triggered, and that event will probably come from the outside, the user or client of the system.

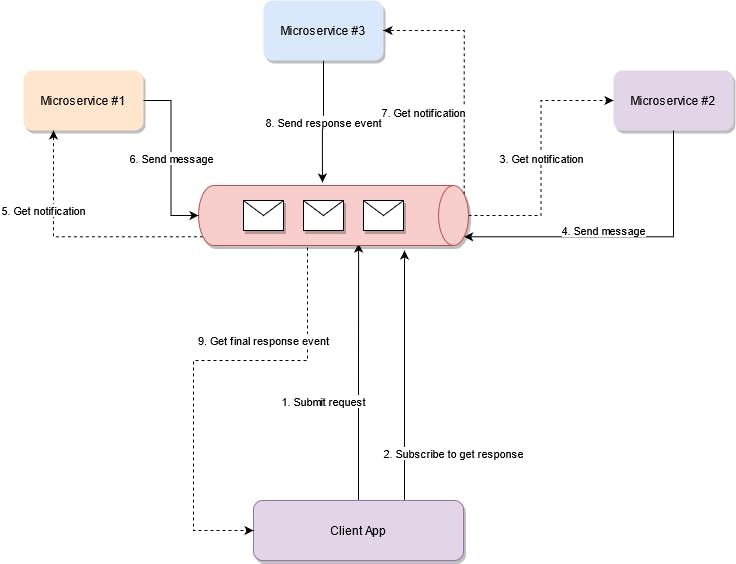

Looking at the above diagram, consider the central red tube to be Redis’ Pub/Sub or a Blocking list, which is a custom implementation of a more reliable Pub/Sub.

The flow starts at #1 with the request submitted by the “Client App” and ends, on 9, by the “Client app” getting notified about the response. The rest? I don’t care, and neither should the client app.

That’s one of the beauties of this paradigm, the architecture becomes a black box for the client. A single request could trigger hundreds of events or just one, the behavior will be the same: once the response is ready, it’ll be delivered to the client. Instead of the client knowing how long it takes or how often it needs to check if it’s ready. None of that matters here.

Keep in mind the following caveats:

- A message is published by its subscriber into a “channel”. It is advised that you have different channels if you want to publish different types of topics. Also if you require extra granularity to distinguish which consumer will have to take care of processing one particular message, the details will need to be part of the message. This is because all subscribers to a channel will get the same messages, so if you have multiple processes listening for and getting the same message, you might end up re-taking the same actions. A flag can be implemented in Redis with the ID of the message (for example), to make sure that the first process to create it, is the one that will take care of processing the event, while the rest can ignore it. This is a reliable way to do it, because setting a key in Redis is an Atomic process, so concurrency will not play a factor in this.

- If there are no subscribers listening for one particular channel, the published messages will get lost. This is the case if you use the Pub/Sub mode, because it works under the “fire & forget” mechanism. If you want to make sure your messages remain there until processed, you can go with the “Blocking list” approach. This solution consists of creating a list directly on Redis’ keyspace (i.e a normal list of values) and have processes subscribe to get keyspace notifications around that key. That way they can decide what to do with the inserted data (i.e if they want to ignore it, process it and remove it, etc).

- If you’re sending a complex message, such as a JSON it needs to be serialized. This is because for both Blocking lists and Pub/Sub the only thing you can send is a string. That being said, if you need to send complex types through the wire without serialization, you could consider using Redis Streams, which is something they allow for. Of course, the restriction there would be that the only allowed types are Redis’ not those of the language you’re using to code the solution.

Let’s now take a look at what happens if your event triggering depends on certain timings.

If you liked what you’ve read so far, consider subscribing to my FREE newsletter “The rambling of an old developer” and get regular advice about the IT industry directly in your inbox

PermalinkTime-based triggering

Another common behavior for reactive architectures, is to be able to trigger certain events after a pre-defined time has passed. For instance: trigger an alert 10 minutes after a problem with the data has been found. Or wait 30 minutes before triggering an alert that an IoT device has stopped sending data.

These are usually behaviors related to real-world restrictions that take a bit of time to solve or that can even solve themselves out by “waiting a little bit” and restarting the countdown in case they do (like an IoT device that has an unreliable connection).

For this scenario, the architecture remains the same, the only difference is that the central communication hub is definitely using the keyspace notifications from Redis.

You see, there are two main features about Redis that you need to understand to get this going:

- When you’re setting a key-value pair, you can optionally define a TTL (Time to Live) in seconds. That turns into a countdown that once it reaches 0, the key will be automatically destroyed.

- When you’re subscribing to a keyspace (this also works on pub/sub, but we’re not using that here), you can subscribe using a pattern. In other words, instead of subscribing to events for the key “last_connection_time_of_device100002”, you can subscribe to “last_connection_time_of_device*”. Then every key that is created and that matches that pattern will notify you once something happens to it.

With both of these things in mind, you can create services that subscribe to these particular keys and react once they are removed (i.e when the event is triggered). While at the same time, you have the producers constantly updating the keys, which also resets the TTL timer. So if you were tracking the last time a device sent its heartbeat, you could have a key per device like I showed above, and keep updated that key every time you get a new heartbeat. Once the TTL is over that means you haven’t received a new heartbeat within the configured period. Your subscribed process will only receive the key name, so if all you need is the ID of the device, you could structure your keys like I showed, and parse the name to capture the desired information.

PermalinkShadow key technique

If on the other hand, you’re saving a complex structure inside that key and you need it, you’ll have to change this approach a bit. This is because when the TTL expires, the key is deleted, and thus the data inside it, so you can’t really retrieve it. This is when instead, you use a technique called “shadow key”.

A shadow key, is essentially a key that is there to trigger the event, but that really is shadowing the actual key that contains the data you need. So back to our example, consider that the producer every time it receives a heartbeat will update 2 keys:

- “last_connection_time_of_device100002” with the unix timestamp of the last received payload from the device.

- “device_data_id100002” with the extra information from the device.

Out of both keys, only the first one will also have a TTL, the second one will not. Thus when you get the expiration notification, you’ll capture the ID from the expired key (last_connection_time_of_device100002) and use it to read the content of the second key. You can then proceed to delete this other key as well if you need to, or leave it there, whatever works for your use case.

The only caveat to consider here, is that if you have Redis configured on Cluster mode, keyspace notifications aren’t propagated throughout the cluster. This means that you’ll have to make sure your consumers connect to every node. Some of these notifications will get lost with no one to receive them otherwise. This is the only downside to this technique, but it’s important to understand it before you spend days debugging your asynchronous logic (been there, done that).

As you can see, the complexity in both cases was reduced to just making sure you subscribe to the correct event or distribution channel. If you were to try and do this with a normal SQL database for instance, you’d have to create a lot of logic around your code to efficiently determine when new data has entered, or when a piece of information was deleted.

Instead, all that complexity here is abstracted by Redis and all you need to worry about, is to code your business logic. That to me is gold.

Have you used Redis for any other scenario outside caching? Share your experience with others in the comments, I’d love to know how you’re all using one of my favorites pieces of tech!

Subscribe to our newsletter

Read articles from The Rambling of an Old Developer directly inside your inbox. Subscribe to the newsletter, and don't miss out.